It’s been just over four months since Europe’s tough new privacy framework came into force. You might believe that little of substance has changed for big tech’s data-hungry smooth operators since then — beyond firing out a wave of privacy policy update spam, and putting up a fresh cluster of consent pop-ups that are just as aggressively keen for your data.

But don’t be fooled. This is the calm before the storm, according to the European Union’s data protection supervisor, Giovanni Buttarelli, who says the law is being systematically flouted on a number of fronts right now — and that enforcement is coming.

“I’m expecting, before the end of the year, concrete results,” he tells TechCrunch, sounding angry on every consumer’s behalf.

Though he chalks up some early wins for the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) too, suggesting its 72 hour breach notification requirement is already bearing fruit.

He also points to geopolitical pull, with privacy regulation rising up the political agenda outside Europe — describing, for example, California’s recently passed privacy law, which is not at all popular with tech giants, as having “a lot of similarities to GDPR”; as well as noting “a new appetite for a federal law” in the U.S.

Yet he’s also already looking beyond GDPR — to the wider question of how European regulation needs to keep evolving to respond to platform power and its impacts on people.

Next May, on the anniversary of GDPR coming into force, Buttarelli says he will publish a manifesto for a next-generation framework that envisages active collaboration between Europe’s privacy overseers and antitrust regulators. Which will probably send a shiver down the tech giant spine.

Notably, the Commission’s antitrust chief, Margrethe Vestager — who has shown an appetite to take on big tech, and has so far fined Google twice ($2.7BN for Google Shopping and staggering $5BN for Android), and who is continuing to probe its business on a number of fronts while simultaneously eyeing other platforms’ use of data — is scheduled to give a keynote at an annual privacy commissioners’ conference that Buttarelli is co-hosting in Brussels later this month.

Her presence hints at the potential of joint-working across historically separate regulatory silos that have nonetheless been showing increasingly overlapping concerns of late.

See, for example, Germany’s Federal Cartel Office accusing Facebook of using its size to strong-arm users into handing over data. And the French Competition Authority probing the online ad market — aka Facebook and Google — and identifying a raft of problematic behaviors. Last year the Italian Competition Authority also opened a sector inquiry into big data.

Traditional competition law theories of harm would need to be reworked to accommodate data-based anticompetitive conduct — essentially the idea that data holdings can bestow an unfair competitive advantage if they cannot be matched. Which clearly isn’t the easiest stinging jellyfish to nail to the wall. But Europe’s antitrust regulators are paying increasing mind to big data; looking actively at whether and even how data advantages are exclusionary or exploitative.

In recent years, Vestager has been very public with her concerns about dominant tech platforms and the big data they accrue as a consequence, saying, for example in 2016, that: “If a company’s use of data is so bad for competition that it outweighs the benefits, we may have to step in to restore a level playing field.”

Buttarelli’s belief is that EU privacy regulators will be co-opted into that wider antitrust fight by “supporting and feeding” competition investigations in the future. A future that can be glimpsed right now, with the EC’s antitrust lens swinging around to zoom in on what Amazon is doing with merchant data.

“Europe would like to speak with one voice, not only within data protection but by approaching this issue of digital dividend, monopolies in a better way — not per sectors,” Buttarelli tells TechCrunch.

“Monopolies are quite recent. And therefore once again, as it was the case with social networks, we have been surprised,” he adds, when asked whether the law can hope to keep pace. “And therefore the legal framework has been implemented in a way to do our best but it’s not in my view robust enough to consider all the relevant implications… So there is space for different solutions. But first joint enforcement and better co-operation is key.”

From a regulatory point of view, competition law is hampered by the length of time investigations take. A characteristic of the careful work required to probe and prove out competitive harms that’s nonetheless especially problematic set against the blistering pace of technological innovation and disruption. The law here is very much the polar opposite of ‘move fast and break things’.

But on the privacy front at least, there will be no 12 year wait for the first GDPR enforcements, as Buttarelli notes was the case when Europe’s competition rules were originally set down in 1957’s Treaty of Rome.

He says the newly formed European Data Protection Board (EDPB), which is in charge of applying GDPR consistently across the bloc, is fixed on delivering results “much more quickly”. And so the first enforcements are penciled in for around half a year after GDPR ‘Day 1’.

“I think that people are right to feel more impassioned about enforcement,” he says. “We see awareness and major problems with how the data is treated — which are systemic. There is also a question with regard to the business model, not only compliance culture.

“I’m expecting concrete first results, in terms of implementation, before the end of this year.”

“No blackmailing”

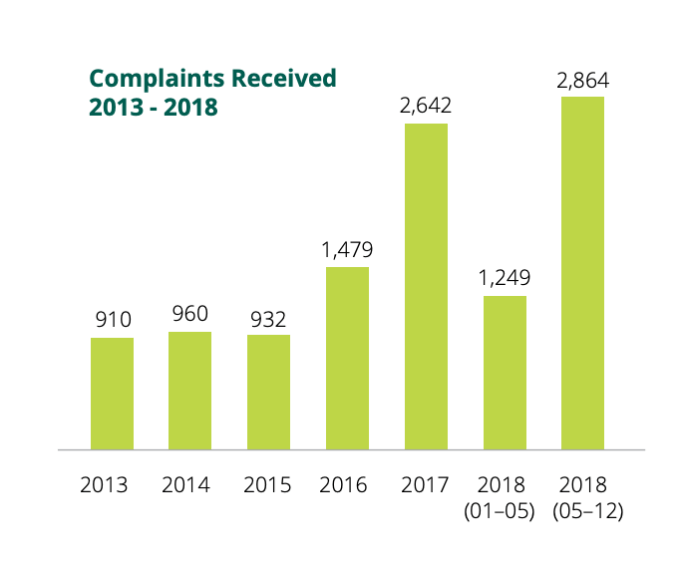

Tens of thousands of consumers have already filed complaints under Europe’s new privacy regime. The GDPR updates the EU’s longstanding data protection rules, bringing proper enforcement for the first time in the form of much larger fines for violations — to prevent privacy being the bit of the law companies felt they could safely ignore.

The EDPB tells us that more than 42,230 complaints have been lodged across the bloc since the regulation began applying, on May 25. The board is made up of the heads of EU Member State’s national data protection agencies, with Buttarelli serving as its current secretariat.

“I did not appreciate the tsunami of legalistic notices landing on the account of millions of users, written in an obscure language, and many of them were entirely useless, and in a borderline even with spamming, to ask for unnecessary agreements with a new privacy policy,” he tells us. “Which, in a few cases, appear to be in full breach of the GDPR — not only in terms of spirit.”

He also professes himself “not surprised” about Facebook’s latest security debacle — describing the massive new data breach the company revealed on Friday as “business as usual” for the tech giant. And indeed for “all the tech giants” — none of whom he believes are making adequate investments in security.

“In terms of security there are much less investments than expected,” he also says of Facebook specifically. “Lot of investments about profiling people, about creating clusters, but much less in preserving the [security] of communications. GDPR is a driver for a change — even with regard to security.”

Asked what systematic violations of the framework he’s seen so far, from his pan-EU oversight position, Buttarelli highlights instances where service operators are relying on consent as their legal basis to collect user data — saying this must allow for a free choice.

Or “no blackmailing”, as he puts it.

Facebook, for example, does not offer any of its users, even its users in Europe, the option to opt out of targeted advertising. Yet it leans on user consent, gathered via dark pattern consent flows of its own design, to sanction its harvesting of personal data — claiming people can just stop using its service if they don’t agree to its ads.

It also claims to be GDPR compliant.

It’s pretty easy to see the disconnect between those two positions.

![]()

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 11: Facebook co-founder, Chairman and CEO Mark Zuckerberg prepares to testify before the House Energy and Commerce Committee in the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill April 11, 2018 in Washington, DC. This is the second day of testimony before Congress by Zuckerberg, 33, after it was reported that 87 million Facebook users had their personal information harvested by Cambridge Analytica, a British political consulting firm linked to the Trump campaign. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

“In cases in which it is indispensable to build on consent it should be much more than in the past based on exhaustive information; much more details, written in a comprehensive and simple language, accessible to an average user, and it should be really freely given — so no blackmailing,” says Buttarelli, not mentioning any specific tech firms by name as he reels off this list. “It should be really freely revoked, and without expecting that the contract is terminated because of this.

“This is not respectful of at least the spirit of the GDPR and, in a few cases, even of the legal framework.”

His remarks — which chime with what we’ve heard before from privacy experts — suggest the first wave of complaints filed by veteran European data protection campaigner and lawyer, Max Schrems, via his consumer focused data protection non-profit noyb, will bear fruit. And could force tech giants to offer a genuine opt-out of profiling.

The first noyb complaints target so-called ‘forced consent‘, arguing that Facebook; Facebook-owned Instagram; Facebook-owned WhatsApp; and Google’s Android are operating non-compliant consent flows in order to keep processing Europeans’ personal data because they do not offer the aforementioned ‘free choice’ opt-out of data collection.

Schrems also contends that this behavior is additionally problematic because dominant tech giants are gaining an unfair advantage over small businesses — which simply cannot throw their weight around in the same way to get what they want. So that’s another spark being thrown in on the competition front.

Discussing GDPR enforcement generally, Buttarelli confirms he expects to see financial penalties not just investigatory outcomes before the year is out — so once DPAs have worked through the first phase of implementation (and got on top of their rising case loads).

Of course it will be up to local data protection agencies to issue any fines. But the EDPB and Buttarelli are the glue between Europe’s (currently) 28 national data protection agencies — playing a highly influential co-ordinating and steering role to ensure the regulation gets consistently applied.

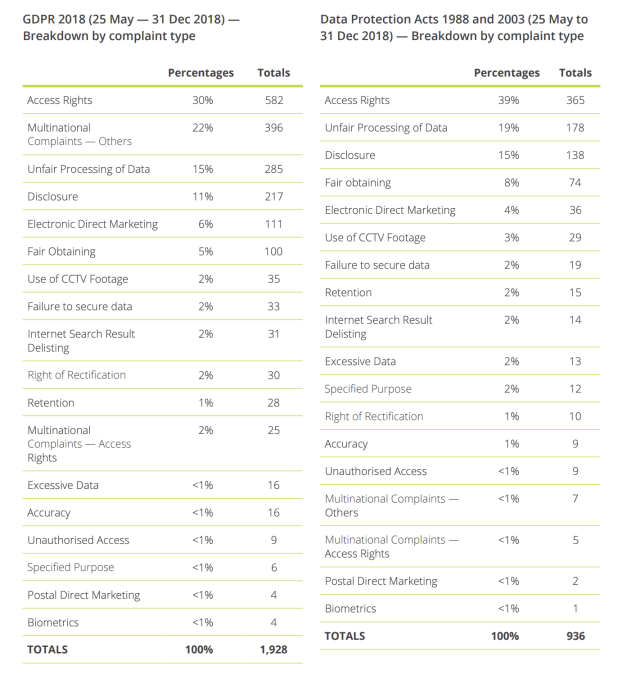

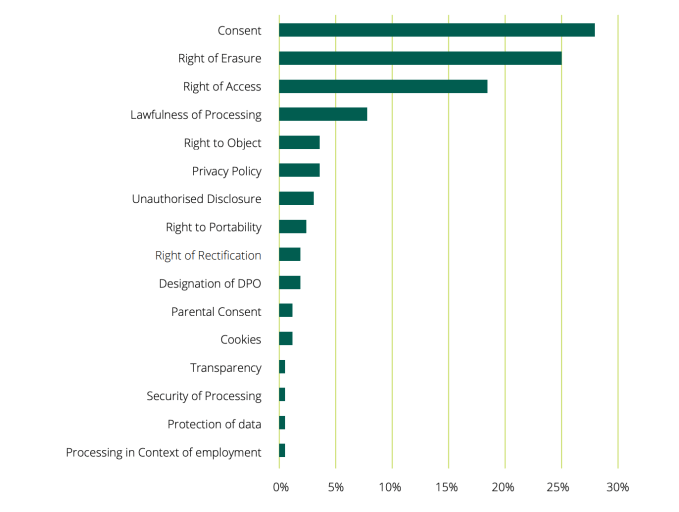

He doesn’t say exactly where be thinks the first penalties will fall but notes a smorgasbord of issues that are being commonly complained about, saying: “Now we have an obvious trend and even a peak, in terms of complaints; different violations focusing particularly, but not only, on social media; big data breaches; rights like right of access to information held; right to erasure.”

He illustrates his conviction of incoming fines by pointing to the recent example of the ICO’s interim report into Cambridge Analytica’s misuse of Facebook data, in July — when the UK agency said it intended to fine Facebook the maximum possible (just £500k, because the breach took place before GDPR).

A similarly concluded data misuse investigation under GDPR would almost certainly result in much larger fines because the regulation allows for penalties of up to 4% of a company’s annual global turnover. (So in Facebook’s case the maximum suddenly balloons into the billions.)

The GDPR’s article 83 sets out general conditions for calculating fines — saying penalties should be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”; and they must take into account factors such as whether an infringement was intentional or negligent; the categories of personal data affected; and how co-operative the data controller is as the data supervisor investigates.

For the security breach Facebook disclosed last week the EU’s regulatory oversight process will involve an assessment of how negligent the company was; what response steps it took when it discovered the breach, including how it communicated with data protection authorities and users; and how comprehensively it co-operatives with the DPC’s investigation. (In a not-so-great sign for Facebook the Irish DPC has already criticized its breach notification for lacking detail).

As well as evaluating a data controller’s security measures against GDPR standards, EU regulators can “prescribe additional safeguards”, as Buttarelli puts it. Which means enforcement is much more than just a financial penalty; organizations can be required to change their processes and priorities too.

And that’s why Schrems’ forced consent complaints are so interesting.

Because a fine, even a large one, can be viewed by a company as revenue-heavy as Facebook as just another business cost to suck up as it keeps on truckin’. But GDPR’s follow on enforcement prescriptions could force privacy law breakers to actively reshape their business practices to continue doing business in Europe.

And if the privacy problem with Facebook is that it’s forcing people-tracking ads on everyone, the solution is surely a version of Facebook that does not require users to accept privacy intrusive advertising to use it. Other business models are available, such as subscription.

But ads don’t have to be hostile to privacy. For example it’s possible to display advertising without persistently profiling users — as, for example, pro-privacy search engine DuckDuckGo does. Other startups are exploring privacy-by-design on-device ad-targeting architectures for delivering targeted ads without needing to track users. Alternatives to Facebook’s targeted ads certainly exist — and innovating in lock-step with privacy is clearly possible. Just ask Apple.

So — at least in theory — GDPR could force the social network behemoth to revise its entire business model.

Which would make even a $1.63BN fine the company could face as a result of Friday’s security breach pale into insignificance.

Accelerating ethics

There’s a wrinkle here though. Buttarelli does not sound convinced that GDPR alone (even combined with the ePrivacy Regulation which is intended to update rules governing digital communications but whose progress has been blocked by dispute and lobbying) will be remedy enough to fix all privacy hostile business models that EU regulators are seeing. Hence his comment about a “question with regard to the business model”.

And also why he’s looking ahead and talking about the need to evolve the regulatory landscape — to enable joint working between traditionally discrete areas of law.

“We need structural remedies to make the digital market fairer for people,” he says. “And therefore this is we’ve been successful in persuading our colleagues of the Board to adopt a position on the intersection of consumer protection, competition rules and data protection. None of the independent regulators’ three areas, not speaking about audio-visual deltas, can succeed in their sort of old fashioned approach.

“We need more interaction, we need more synergies, we need to look to the future of these sectoral legislations.”

People are targeted with content to make them behave in a certain way. To predict but also to react. This is not the kind of democracy we deserve. Giovanni Buttarelli, European Data Protection Supervisor

The challenge posed by the web’s currently dominant privacy-hostile business models is also why, in a parallel track, Europe’s data protection supervisor is actively pushing to accelerate innovation and debate around data ethics — to support efforts to steer markets and business models in, well, a more humanitarian direction.

When we talk he highlights that Sir Tim Berners-Lee will be keynoting at the same European privacy conference where Vestager will appear at — which has an overarching discussion frame of “Debating Ethics: Dignity and Respect in Data Driven Life” as its theme.

Accelerating innovation to support the development of more ethical business models is also clearly the Commission’s underlying hope and aim.

Berners-Lee, the creator of the World Wide Web, has been increasingly strident in his criticism of how commercial interests have come to dominate the Internet by exploiting people’s personal data, including warning earlier this year that platform power is crushing the web as a force for good.

He has also just left his academic day job to focus on commercializing the pro-privacy, decentralized web platform he’s been building at MIT for years — via a new startup, called Inrupt.

Doubtless he’ll be telling the conference all about that.

“We are focusing on the solutions for the future,” says Buttarelli on ethics. “There is a lot of discussion about people becoming owners of their data, and ‘personal data’, and we call that personal because there’s something to be respected, not traded. And on the contrary we see a lot of inequality in the tech world, and we believe that the legal framework can be of an help. But will not give all the relevant answers to identify what is legally and technically feasible but morally untenable.”

Also just announced as another keynote speaker at the same conference later this month: Apple’s CEO Tim Cook.

In a statement on Cook’s addition to the line-up, Buttarelli writes: “We are delighted that Tim has agreed to speak at the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners. Tim has been a strong voice in the debate around privacy, as the leader of a company which has taken a clear privacy position, we look forward to hearing his perspective. He joins an already superb line up of keynote speakers and panellists who want to be part of a discussion about technology serving humankind.”

So Europe’s big fight to rule the damaging impacts of big data just got another big gun behind it.

![]()

Apple CEO Tim Cook looks on during a visit of the shopfitting company Dula that delivers tables for Apple stores worldwide in Vreden, western Germany, on February 7, 2017. (Photo: BERND THISSEN/AFP/Getty Images)

“Question is [how do] we go beyond the simple requirements of confidentiality, security, of data,” Buttarelli continues. “Europe after such a successful step [with GDPR] is now going beyond the lawful and fair accumulation of personal data — we are identifying a new way of assessing market power when the services delivered to individuals are not mediated by a binary. And although competition law is still a powerful instrument for regulation — it was invented to stop companies getting so big — but I think together with our efforts on ethics we would like now Europe to talk about the future of the current dominant business models.

“I’m… concerned about how these companies, in compliance with GDPR in a few cases, may collect as much data as they can. In a few cases openly, in other secretly. They can constantly monitor what people are doing online. They categorize excessively people. They profile them in a way which cannot be contested. So we have in our democracies a lot of national laws in an anti-discrimination mode but now people are to be discriminated depending on how they behave online. So people are targeted with content to make them behave in a certain way. To predict but also to react. This is not the kind of democracy we deserve. This is not our idea.”

“Official Visit to Washington D.C and San Francisco”

“Official Visit to Washington D.C and San Francisco”